Values and frames of reference that inform Birdability’s work

Values are a set of principles or standards that a person or organization views as important. They often guide our decision-making, and when we share similar values with others we often get along with them. Frames of reference are a set of beliefs, ideas and values from which a judgement can be made. Does this make sense to me? Yes, because it is inline with my cultural frame of reference.

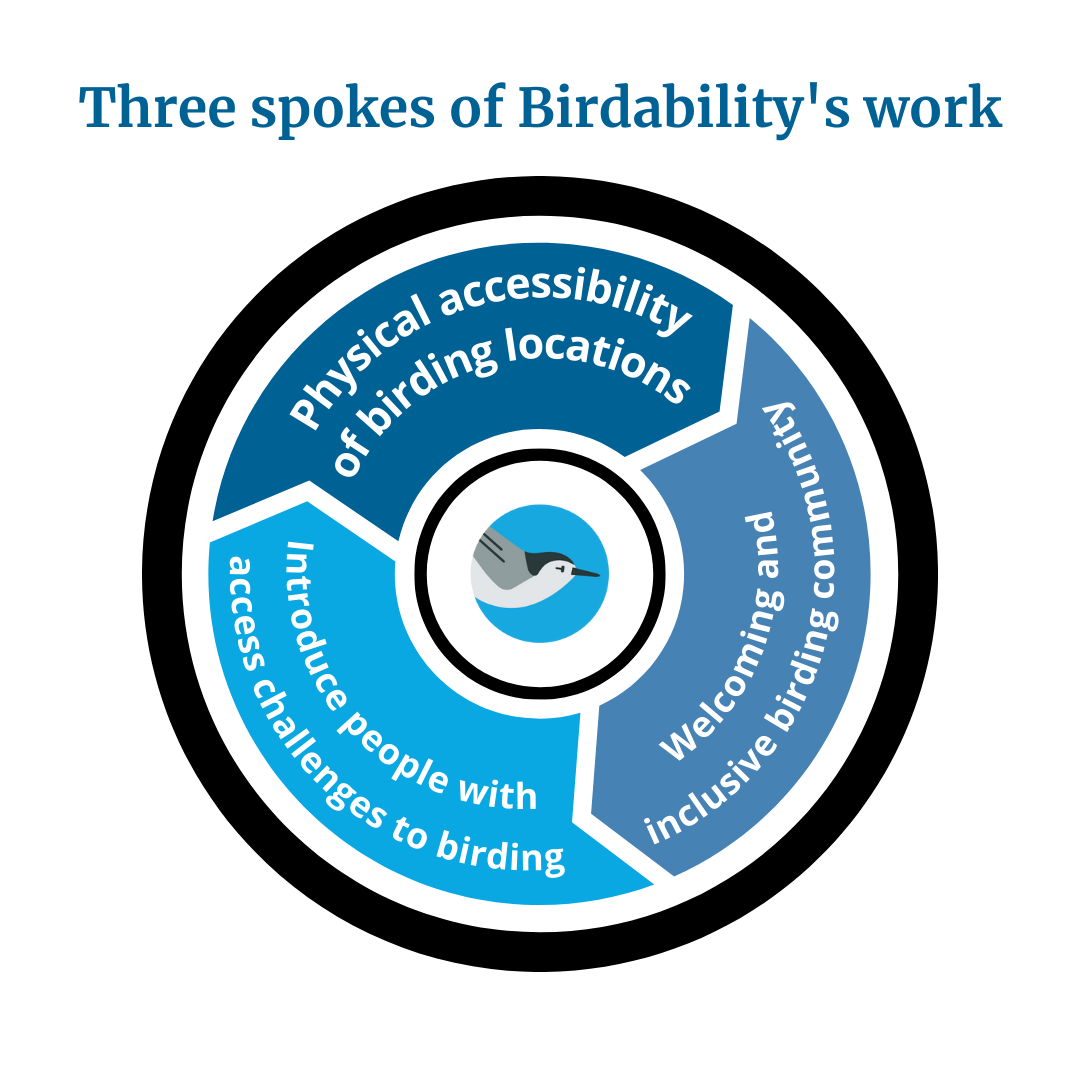

Birdability’s three spokes — improving the physical accessibility of birding locations, empowering a welcoming and inclusive birding community, and introducing people with access challenges to birding — are the actions we take; the things we do. Our values and frames of reference inform the way we approach this work — they are our guiding principles.

Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Access (IDEA)

We believe that every body should be included in decision-making, whether that’s making decisions about trail design, programming or events planning, or the ways we communicate. We believe diversity is beautiful, and it is our differences in outlooks, life experiences, approaches and cultural backgrounds that make us each so interesting and amazing, individually and collectively. We believe that everybody should be treated fairly and justly (this is equality), but that folks from groups who have been historically marginalized may need an extra boost just to start at the same place as someone with some level of inherent privilege (this is called equity). We believe that everybody should have the same access to birding locations, programs, and life opportunities; physical accessibility is something we must prioritize and work hard on for folks with disabilities and other health concerns.

The disability community

Participants on an accessible outing, Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson, Arizona. Photo: Freya McGregor.

This is who we are. This is who we serve. The phrase “Nothing about us, without us,” came from the disability rights movement in the 1970s — stop telling us what we need and doing it to us; let us be part of the decision-making and the action. The disability community is an incredibly diverse group of people with all kinds of access needs and all kinds of lived experiences. We follow this community’s lead. For example, the cultural shift in preferred language from ‘handicapped’ to ‘disabled’ has been spearheaded by the disability community: “Just say ‘disabled’, it’s not a dirty word.” So, we do. Many members of the autistic community prefer identity-first language (“I am an autistic person,”) over person-first language (“I am a person with autism,”), so we say that too. (There’s more on inclusive language use in our Guidance Documents.) We do our best to listen, learn and apply, in order to serve our people the best we can.

The Ten Principles of Disability Justice

Created by Sins Invalid in 2015, the Ten Principles of Disability Justice frame the ways we can all work towards equity and justice for the disability community. It includes statements such as Recognizing Wholeness — knowing and appreciating that people with disabilities should be shown the basic human dignity of being acknowledged as a complete person. Another principle, Commitment to Cross-disability Solidarity, encourages the diverse groups of people who make up the disability community to work together for and with each other towards our collective justice. We encourage you to learn more about these principles, and apply them to your own work.

The social model of disability

The medical model of disability views disability as something broken that needs fixing. This makes sense when someone has a broken leg — repairing that leg is a good thing to do! Many folks with chronic illness identify with this frame of reference, especially if they have a chronic illness, and medication (the ‘fix’) helps. Many other folks with disabilities identify more closely with the social model of disability. This frame of reference says that there’s nothing inherently wrong with being disabled, and you don’t need fixing. In fact, it is not the person who is disabled, but the environment that is disabling. If a wheelchair user cannot get into a building because there are steps and no ramp, it is not because there’s a problem with the wheelchair user. It’s because the built environment is the problem. (After all, if there was an appropriate ramp they would have no trouble!)

At Birdability, we operate from this lens. What is it about the environment that is disabling, and how can we address it so that it instead invites participation and inclusion? What can we do about the physical accessibility of birding locations? How can we help the social, cultural and institutional environments of birding be empowering, rather that exclusionary? We’re not in the business of ‘fixing’ a person; instead, we want to positively impact their world!

Positive impacts

Speaking of being positive, this value is really important. We don’t want to just ‘Do no harm’; instead we want to make a positive difference and do Good Things. This value informs everything we do in a grand scale, and in smaller ways too. We encourage people to advocate for accessibility improvements in their own communities, but not in a, “This is awful, your visitor center sucks!” way. We believe in approaching it from a positive angle: “This nature center is so wonderful. There are so many birds! Unfortunately, there are a few things that make the visitor center really challenging to access for folks with disabilities. This is what I noticed, and this is what you could do to help improve it.”

We’re not about toxic, or forced, positivity, but we find that others tend to be drawn to friendly, positive people. We’ve noticed that folks are more likely to engage with, and try to help, if you’re cheerful and come with some potential solutions, rather than just point out all the flaws. We all have a circle of influence, and we can all have positive impacts on the world around us. Yes, some people’s circles are larger than others, but we all have one!

Empowering others

Working directly with our local communities, we could not bring about the change we want to see across the US (and the world!) by ourselves — it just wouldn’t be possible. What we can do is empower others in this work, so they feel inspired and equipped to act in their own communities.

One way we do this is by creating the freely available Guidance Documents on this website. That way, anyone who wants to learn more about being a welcoming and inclusive birder can learn what we’ve learnt, and anyone who’s organizing accessible bird outings can find out what information to include when they’re writing up the event’s description, for example. We share our own knowledge and create the tools necessary to do this work so that others can do it too. Our Birdability Captains (our volunteers) are particularly invested in this, and we have monthly meetings and other supports to continue to encourage and empower them, too.

We also want to empower birders (and potential future birders) with access challenges! Having a disability or another health concern can be very disempowering. Not having control over your body or mind, having people make decisions about you without your input, and being unable to visit places because access was not a priority are common experiences. We also know that navigating a new trail, or working through a tricky bird ID can be very empowering. We know that exploring and adventuring, far from home or nearby, can be empowering too. (In fact, this was the theme of one of the panels during Birdability Week 2021.) We want to encourage folks with access challenges to try new things and get out of their comfort zone; we want people to feel like they can!

Sharing resources

We spend a lot of time creating the resources on our website. We do this to empower others and to share what we know. We have been asked why we don’t charge for such valuable information, but removing financial barriers to access enables more people to participate, and we want as many people as possible on board with this work! Putting it out into the world — through our website, social medial, presentations and newsletters — helps others learn too. And, to paraphrase Maya Angelou, when we know better we can do better.

We also do our best to support local birding groups who work intentionally in their communities to create opportunities for BIPOC, LGBTQIA+ and disabled birders through our Good IDEA for Birding community. This work can be amazing, but it can also feel isolating, and sharing what we have learnt with others who have similar values helps us all reach our goals sooner. Over the last year we have learnt a lot about setting up and running a nonprofit, and it’s easy to share what we’ve learnt with, for example, the BIPOC Birding Club of Wisconsin, as they work towards nonprofit status themselves. We believe that when we work together and uplift and support each other, we all win.

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy (OT) is a healthcare profession that’s all about helping folks do the things in their everyday life (their occupations) that bring them meaning, but that they’re having trouble doing because of a disability, injury or illness. Often it’s activities like getting dressed without needing help, or learning how to navigate public transport so they can get to work… but at Birdability, it’s all about birding.

the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance states that there are three categories of occupations: productivity (usually work, school or volunteering), leisure (anything fun, like birding!) and self-care (eating, sleeping, brushing your teeth… and maybe birding too). It also states that every occupation occurs within four different environments: the physical environment, the cultural environment, the social environment and the institutional environment. OTs can impact one or more of these environments to support participation; if you’re familiar with our work, you’ve probably seen this happening! (Those links in the previous sentence connect to some of the ways we’re addressing each environment in our work.) To empower participation, OTs can also teach the person or the people around them new skills, and we can provide adaptive equipment. OTs are client-centered, and are trained in health promotion and program development. All of these things inform what, and how, we work at Birdability.

Intersectionality

Black disabled birders exist! If we want to be welcoming and inclusive, we must address racism and safety in birding, as well as disability-specific issues. Photo: Melanie Furr.

Originally discussed by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1991 in relation to the compounding issues that people who are both Black and female experience, this concept states that we are not one-dimensional humans. We each hold multiple identities, but when they include multiple historically marginalized identities (someone who is Black, disabled and gay, for example) these combine to have an even more significant impact on that person in a negative way. The intersecting systems of oppression — the multiple layers of social injustice — mean, for example, that someone who is Black, disabled and gay may have to deal with racial micro aggressions, inadequate physical accessibility and homophobia when trying to go birding with a group.

Intersectionality means that if, at Birdability, we were only working to serve white, straight, cisgender disabled birders, we wouldn’t be truly inclusive, and we wouldn’t be doing our job. Intersectionality means that we must address racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, classism, xenophobia and all the other awful discriminatory mindsets in the cultural and social environments that can negatively impact someone’s ability to go birding. (There’s more about this in a Birdability Blog post titled Why we have a safety question in the new Birdability Site Review.) While we don’t work explicitly to make birding more accessible for nondisabled People of Color, for example, we must be working to make birding more accessible for disabled People of Color… which hopefully creates some positive follow-on effects for People of Color without access challenges.

The power of representation

One of our Birdability Captains, Jerry Berrier, models the Bird Collective x Birdability t-shirt. He is totally blind, and is using a long cane and a microphone to enjoy birds — not a pair of binoculars. And have a look at who else is represented on that t-shirt! Photo: Lee Berrier.

When you see someone who looks or sounds like you, it feels good. Seeing a part of your identity represented in a group you’re interested in joining, or in an ad for an outdoor company, is powerful. It can help you know that you’re safe and welcome in this space. It can send you a message of, “I can do that too!” It matters. If you’re white and able-bodied and you live in North America, Australia or the UK, the chances are that you’ve never really had to think about this much, because in these white-dominated societies this just happens.

If you’re a white, young, female birder, you might have noticed how often photos of birders show mostly nondisabled older men, and rarely any young women. It’s easy to be unsure, in this situation, if younger people are invited to participate. It’s also not surprising when people outside the birding community think birders are all retirement-age, nondisabled white people. What messaging does this send BIPOC, LGBTQIA+ or disabled would-be birders?

It’s likely that folks who have a visible disability, or who are BIPOC or LGBTQIA+, are well aware of how often they do not get to see themselves represented in photos of bird festival outings, or in ads from optics companies, or in a lineup of speakers for an online program. Kids holding these identities, in particular, may not realize (often unconsciously) that they, too, can be birders, if they only only see older walking people birding, for example, and never anyone using a power wheelchair. We want more photos of birders with access challenges, and of birders who share multiple marginalized identities, out in the world, on birding and nature organizations’ Boards, leading outings, and amplified by birding magazines. Because representation matters!

Universal design

The incredibly accessible observation building at Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge, Alabama, demonstrates the principles of universal design, allowing everybody to enjoy the Sandhill Cranes overwintering there. Photo: Freya McGregor.

Not everything is well-thought-out. The 7 Principles of Universal Design guide designers — of places, of objects, and even of teaching — to create environments, products and learning opportunities that the greatest number of people will be able to access successfully with the least effort. Universally designed birding locations allow equitable access regardless of disability, and will include interpretive signs with tactile and audio components — not just visual information. (Learn more about what makes up a truly accessible birding location here.) Well-designed products will be will be intuitive and easy to use, will have a margin of error built in, and will require low physical effort to carry and use.

Universal design benefits people with disabilities and other health concerns, and it benefits everybody else, too. That’s why we advocate for tactile components on interpretive signs — it’s not only folks who are blind or have low vision who might benefit, but young kids, people with print disabilities like dyslexia, folks who don’t read English and people who just enjoy touching things to help them learn! And accessible port-a-potties let everybody in, but the regular-sized ones only allow some people to use the bathroom. When you apply universal design principles, every body wins!

What are your values? What frames of reference do you use to help make decisions in your life? Do any of them align with ours? We hope so, and we’re glad you’re here! We hope you’ll continue exploring our website and helping us ensure that birding and the outdoors truly are for everybody and every body!

If you or your organization believe in similar values and that this work is important, please consider donating to support us as we continue to ensure that birding truly is for every body. Thank you!

Photo in page header: Taken at the Shepherd Center Spring Birding Retreat, by Melanie Furr.